In the wake of the January 2011 Sandy River storm event that caused significant channel migration, bank erosion, and impact to multiple communities, the Sandy River Basin Watershed Council (SRBWC) initiated a series of community dialogs and field explorations as the first phase of Restorative Flood Response (RFR). Through this project’s technical assistance, local awareness of potential risk and impact has grown into a broader understanding that storm impact on the Sandy occurs through channel migration and lateral erosion, often outside of the legally defined flood zone.

Restorative Flood Response Phase I explored ways to work within the Sandy’s dynamic natural behavior to achieve restoration and risk reduction together. Restoration experts, agency biologists, and impacted community residents joined in a review of river and restoration science to define restoration-based floodplain and streambank actions that enhance habitat and also may reduce flood risk. Traditional hardening practices have proven to be ineffective against storm impact during extreme weather events, so a key project objective was to help residents understand alternatives to streambank hardening. This first phase of RFR succeeded in gathering interested and willing coalition of neighbors to learn more about these habitat-positive practices and put them to use.

Restorative Flood Response Phase I sought consensus around practices to meet several goals:

Restorative – any actions contribute to improved ecological conditions for listed salmonids, emphasizing floodplain connectivity and the positive role of large wood in habitat formation;

Risk Reducing – Private landowners and land management agencies recognize the risk and future vulnerability of roads, bridges, sewer and water systems, and other infrastructure, so actions should work within riverine processes to reduce future risk;

Durable/Affordable – actions must be designed with to withstand the Sandy’s dynamic nature and scaled and located appropriately to work within the process of channel migration; landowners and public agencies can only invest in measures that are affordable for the long-term, and combining efforts among landowners can lead to shared investment; and

Equitable – reach scale analysis and solution development can provide equity to adjacent, upstream/downstream landowners, and avoid “passing the buck” by shifting impacts through traditional single site streambank hardening. Multiple landowner, collaborative projects can spread the cost and benefits of enhancements among multiple stakeholders.

The intersection of priority habitat restoration zones and the impacted areas from recent storms requires a new approach to flood response. This project explored applying habitat restoration approaches in the wake of flood damage to developed areas by improving the community’s understanding of river dynamics. Collaboration between adjacent landowners is critical to this new approach of RFR. To cooperatively address flood preparedness issues and move forward with habitat-positive solutions to reduce flood risk where possible, the conversation requires input from landowners, agencies, and technical experts.

With assistance from technical experts in geomorphology, engineering, and restoration design, RFR participants explored potential actions that would restore floodplain processes and enhance habitat conditions for wild fish, while reducing future erosion and channel migration risk. RFR Phase I emphasized that floodplain connection, habitat diversity, large wood log jams and other features of restoration can also reduce risk for homeowners and infrastructure. Reconnecting upstream areas isolated by historic actions may dissipate erosive force in future high water events, and actions that are coordinated among landowners may reduce unintended adverse impacts from single-landowner projects.

Restorative Flood Response Phase I succeeded in several respects. We defined a demonstration project with participants for Restorative Flood Response Phase II, including floodplain reconnection in a residential neighborhood. We helped catalyze efforts by Clackamas County to develop restorative, community-based flood responses, including the county’s agency projects and development standards, as well as an erosion study to develop design standards for the Sandy. And most importantly, technical assistance through this project significantly raised public awareness and understanding of the potential and need for restorative streambank actions on the Sandy. The project recognized significant future community investment that can be steered toward practices that benefit habitat for listed salmonids, as well as the long-term sustainability of local communities.

Background

The Sandy’s dynamic, glacial fed environment can create volatile conditions during high flow events, driving a process now recognized as channel migration. Floods do not merely raise and lower the river level, but can cause the river’s entire main channel to shift, as the river’s energy during high water events disperses flow into remnant, historic channels or carves new ones in the volcanic, unconsolidated lahars that make up much of the Sandy floodplain and its underlying geology. Such high water events, and the channel migration they cause, are natural elements in the habitat for threatened salmon and steelhead, but create several challenges for restoration, infrastructure and private landowners along the Middle and Upper Sandy. The January 16-17, 2011 high water event brought riverside landowners an acute reminder of the Sandy River's dynamic power. Approximately 9 inches of rain fell at Timberline Lodge on Mt. Hood, causing the mainstem Sandy channel to migrate up to hundreds of feet within the floodplain, carrying thousands of pieces of large woody debris and undermining stream banks and nearby structures.

The January 2011 high water event was the third largest on record, but at least the 6th time since 1996 that the river has exceeded 18,000 cubic feet per second (two additional such storms occurred in winter 2011-2012), a level that can cause significant erosion. The 2011 storm caused major impacts to the river’s shorelines as well as public and private infrastructure in developed areas. In the upper and middle Sandy, several houses were destroyed, others significantly damaged. Clackamas County Water Environment Services saw an effluent diffuser in the Sandy from its Hoodland treatment station destroyed and a pump station near the Timberline Rim neighborhood rendered temporarily inoperable by inundation. A half-mile section of Lolo Pass Road, serving hundreds of residents and representing a safety access for upstream land managers and utilities, was washed out, and several bridge footings made vulnerable requiring temporary road closures and diversions. Lateral erosion due to channel migration, and the resulting undermining of homes and infrastructure, is the primary property impact of the high water events on the Sandy (rather than inundation of structures).

Coming on the heels of significant high water events in 1996, 1998, 1999, 2006, 2008, and 2009, the Sandy’s storm intensity and frequency have focused additional concern from area residents and public agencies. Sandy residents and land managers began to recognize that traditional river hardening – rip rap, levees, and revetments -- were proving ineffective at the least, and possibly intensifying erosion.

In the Sandy, a basin that is the focus of habitat restoration efforts for ESA listed Salmon and Steelhead, agencies and residents also recognized that hardened banks create no habitat value. Although providing some temporary measure of protection for individual landowners, hardened banks on individual properties likely worsen reach scale problems of streambank erosion by funneling energy in a slingshot effect against opposite, downstream banks. Much of the impact from the January 2011 storm impacted river reaches prioritized for habitat restoration by the Sandy River Basin Partners. The middle and upper Sandy River reaches provide habitat for spring and fall Chinook, coho, and winter steelhead and serve as important migration corridors for adults and juveniles moving to the Zigzag River, Clear Fork of the Sandy, Still Creek and other highly productive tributaries. The Sandy River Basin Characterization Report (Sandy River Basin Partners 2005) states that the middle Sandy contains about 24 stream miles of habitat that are currently used by anadromous fish, about 14 percent of the total stream miles (170 miles) currently used by anadromous fish in the Sandy River Basin, compared to 37 miles historically. From a restoration perspective, the Middle Sandy River Watershed ranks highest among the six watersheds in the Sandy River Basin for (1) spring Chinook abundance and productivity, (2) fall Chinook productivity, and (3) coho abundance and ranks second highest for fall Chinook and winter steelhead abundance and coho productivity. The Characterization report rated the middle Sandy’s restoration potential as “quite high”, and identified insufficient stream structure, reduced large wood, and habitat diversity and sediment load as limiting factors, with “a high effect in depressing productivity in several reaches along the mainstem Sandy River (Sandy River Basin Partners, 2005; pg 5-15, 5-22).”

SRBWC initiated a series of community dialogs and field explorations in 2012 as the first phase of RFR (OWEB TA grant 212-3006). The question of which actions could pose as appropriate Restorative Flood Response measures in specific affected river reaches requires additional investigation. Private landowners lack the technical resources to analyze reach scale river processes or to coordinate actions among adjacent landowners. While reach-scale actions involving multiple properties likely would create the most effective, durable solutions, individual property owners lack the ability to effectively coordinate actions and resources to enhance habitat and reduce risk from future high water events.

During RFR Phase I, landowners pointed to the need for Sandy basin examples of effective, restorative actions they could emulate and repeat. Some participants in our community engagement process pointed out that we have the opportunity to do things now that consider the big picture (river processes, climate change, etc.) as we work together to take actions that will provide long-term benefits for people and the river. The challenge for landowners is how to design and where to apply engineering solutions that benefit habitat, while reducing risk to developed areas and infrastructure. Feasibility also depends on identifying actions that comply with prescriptive local, state, and federal permit requirements that support Endangered Species Act recovery goals. As one community leader noted, “We are willing to do the right thing if someone can help us to understand what that is and how to do it.” During Phase I of our RFR project many landowners have requested guidance on the types of projects that are suited to the dynamic Sandy, can be permitted under the Regional General Permit issued by the Army Corps (developed following the 2011 event to expedite Corps review of streambank stabilization actions that go beyond riprap), and that will not adversely impact habitat.

Description of the Work

During RFR Phase I in 2012 we conducted two community meetings with local residents, technical experts, and restoration practitioners including ODFW and US Forest Service fisheries biologists, USFWS geomorphologist Janine Castro, noted engineer/geomorphologist Dr. Tim Abbe, and technical consultant staff of both Cardno Entrix and Interfluve. Sandy River Basin Watershed Council staff and experts met with homeowners in four neighborhoods that were impacted by the January 2011 event, considering potential reach-level streambank and floodplain actions to improve habitat and reduce future risk. We held a workshop during our 2012 Sandy River Restoration Expo that featured a floodplain specialist from the Clackamas County planning department, and produced and distributed a CD containing maps, streamside planting information, USGS papers on Mt. Hood’s lahars and other resources for riverfront residents. A total of approximately 90 residents have participated in these meetings and site visits.

First Community Meeting

SRBWC held the kickoff meeting for our Restorative Flood Response project on February 28, 2012 at the Welches Elementary School. The meeting attracted residents from each of the key sections of the upper Sandy River that were impacted during the January 2011 high water event. The purpose of this event was to provide background information for residents and to establish a common framework for thinking about the river. We encouraged concerned residents to recognize that restorative practices would not necessarily deliver safety in future floods, but that a variety of habitat-positive actions could reduce risk in some circumstances, and do so within permit restrictions.

This initial meeting included presentations by a fluvial geomorphologist (Janine Castro from US Fish and Wildlife), a fisheries biologist (Todd Alsbury from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife), and a river restoration consultant (Tim Abbe of Cardno-Entrix). Audience members engaged in active participation, as the meeting has breakout groups with questions and thoughts gathered throughout. The speakers highlighted some of the realities that influence potential projects on the Sandy River, and presentation summaries are as follows:

Fish and Wildlife Service expert Janine Castro introduced the Sandy’s high energy behavior stemming from the steep gradient from high on Mt. Hood down to the river segment from Old Maid Flat to the confluence of the Sandy and Salmon Rivers. The river flows through a valley filled with unconsolidated deposits from Mt. Hood lahars. This combination of high energy and erosive soils results in channel migration, a process in which the river can cut new channels and move laterally across the floodplain. Erosion, particularly during high water events, is what puts homes, roads and community infrastructure at risk.

Todd Alsbury of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife described the high quality habitat that the Sandy River Basin provides to listed salmon and steelhead and their critical importance to the recovery of native salmon populations in the Lower Columbia Basin. In the Sandy, four species of salmon and trout are listed threatened under the Endangered Species Act: Fall and Spring Chinook salmon, Coho salmon and Winter Steelhead. The middle and upper Sandy River reaches, where residents and infrastructure experienced the greatest flood impacts, provide habitat for Spring Chinook, Coho salmon and Winter Steelhead and serve as important migration corridors for adults and juveniles moving to the Zigzag River, Clear Fork of the Sandy, Still Creek and other highly productive tributaries. Private entities and state and federal agencies have teamed up to protect and restore habitat for those species. Alsbury emphasized the role that habitat restoration can play, the idea that “wood is good”. Although some landowners fear that naturally occurring large logjams present risk, they can also mitigate the impacts of channel migration and provide excellent habitat at the same time.

Dr. Tim Abbe introduced a concept of Restorative Flood Protection, utilizing natural process and actions that work within dynamic river hydrology to accomplish multiple habitat and infrastructure goals. Abbe focused on cumulative benefits from restorative strategies, particularly the natural role of large wood in benefiting habitat and flood risk reduction. The presence of large wood is the basis of stream resilience affecting the type and size of gravel deposition, the erosion potential, and other key process related to both habitat and flood impact. He discussed examples of wood-based stream restoration in the Puyallup and Cle Elum rivers, including potential use of simulated “dolotimber” concrete ballast to reduce cost of engineered channel roughness or streambank wood structures.

Site Visits to Neighborhoods

On March 20, 2012 we made visits to the Timberline Rim, Salmon River Park, Zigzag Village, and Autumn Lane neighborhoods to review issues with residents and walk their section of the Sandy River with them and river restoration experts. Timberline Rim is adjacent to the mainstem Sandy River upstream from the confluence with the Salmon River; Salmon River Park is located on the peninsula at the confluence of the Sandy and Salmon rivers; Zigzag Village includes residents along Lolo Pass Road near the Zigzag River and Sandy Rivers; and Autumn Lane is a community along the mainstem Sandy upstream from the confluence with the Zigzag River.

The purpose of the tours were to gather community input on flood and channel migration impacts in their neighborhoods, identify opportunities and constraints related to positive restorative flood response actions and make technical expertise available. We asked residents to identify impacts to water, sewer, and other infrastructure in their neighborhood during high water events and their concerns regarding channel migration and erosion. The conversations provided an opportunity for two fluvial geomorphologists to answer questions and respond to the issues that were raised.

Residents welcomed us to their neighborhoods for a discussion of their experiences with the Sandy River and the issues they’re facing as a result of channel migration. These discussions utilized maps and areal imagery in the neighborhoods, including photographs of historical time series. The purpose of these site visits was to facilitate a conversation with residents about:

Importance of energy dissipation in river management

Linkage between upstream and downstream bank erosion problems

Alternative flood risk management measures, including the use of large wood as an important solution

Restoration actions, such as the benefit and potential of multi-landowner actions. These could include collective bank treatment (floodplain reconnection and large wood placement) projects as being more durable and ecologically effective, rather than projects that only address a small piece of the river (e.g. one or two residential lots)

Consideration of the potential impact of a project on downstream habitat, infrastructure, and landowners

Timberline Rim

Erosion due to high water has affected homes, the community green space, tennis court and sections of the road. This neighborhood depends upon water and sewer lines that cross beneath the Sandy River that connects two areas of the subdivision on either side of the river. Residents and Clackamas County recognize the utility lines were exposed to greater risk due to the channel migration that occurred in January 2011. Landowners expressed a range of sentiments regarding relocation out of the channel migration and flood risk area. Some have a strong desire to stay in place, whereas others brought up the idea of relocation or land swaps. The typical flood response by riverfront residents is to harden the riverbank in an attempt to protect their homes. Participants noted that additional riprap has been installed in localized areas after each high water event and some riprap work has already been completed since the January 2011 event. Additionally, there was discussion about how the area has changed over time and how the high water events seem to be getting more frequent and intense.

A common assumption remains among some residents that hardened river banks and revetments will provide some benefit during flood events, although structures built after the 1996 flood have required extensive maintenance, and several were compromised in 2011. In the category of “early action” two landowners constructed a stone-heavy reinforcement that incorporated some large wood of their riverfront, which the Corps of Engineers approved under the Regional General Permit that was issued after January 2011.

We discussed the fact that these types of bank hardening projects can be related to future, unintended impacts upstream and downstream and are not ideal for stream habitat. Residents cited their concerns about water and sewer infrastructure, as well as their individual properties. Some residents see that larger, collective projects involving multiple landowners could be beneficial here. Overall they feel that the current flooding threatens private property and some roads within the subdivision, and creates a high potential for channel migration and erosion along the streambank.

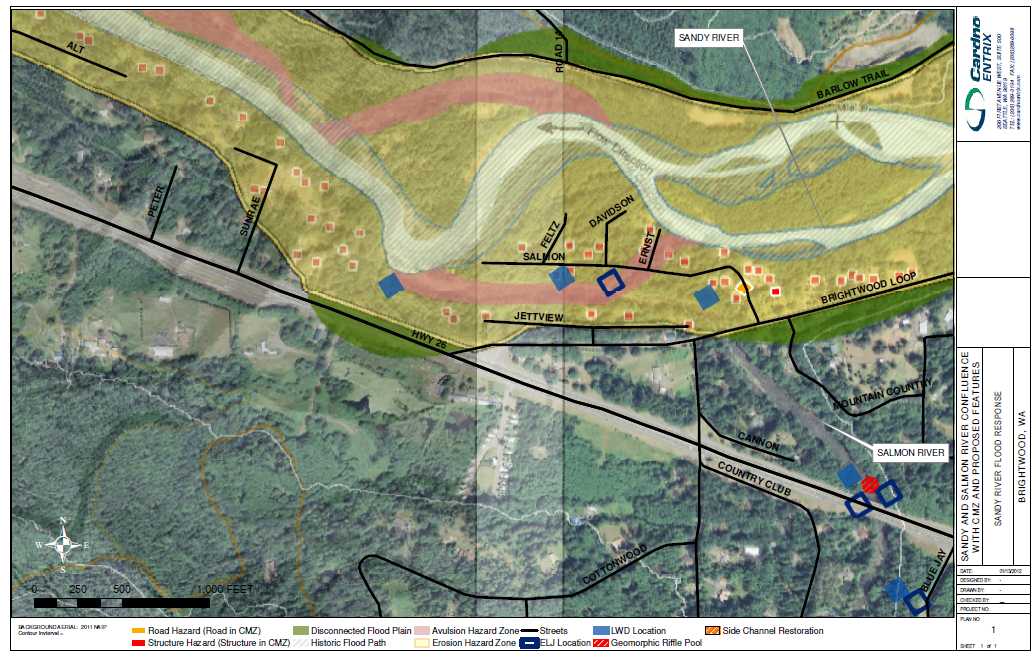

Salmon River Park

We staged two visits with community members at this site, which is located on the peninsula at the confluence of the Sandy and Salmon Rivers and is vulnerable to high flows from both rivers. Residents described the active flood history of the neighborhood as well as what happens during high water events. During the January 2011 event, the Sandy River flowed through a remnant side channel that connects the Sandy and the Salmon Rivers and caused damage to the road and threatened the water system.

Community members expressed some overarching concerns that apply to the general neighborhood. Those attending the meeting shared photos with us from the 1931 flood that impacted their community, showing a pattern of flood in this area. These include the potential risk of flood damage to utilities and important infrastructure and threats to road lifeline arterials. Additionally, potential for channel migration and erosion to the community is a major concern. Residents are concerned about the lack of available resources to address actions that reduce flood impacts, and many feel that they have limited options for reducing the impact of inundation. In addition to these property-related concerns, the presence of ESA listed salmon makes it more complicated to address bank erosion problems

Zigzag Village / Lolo Pass area

This gathering included residents of Zigzag Village as well as some homeowners who live between Zigzag Village and the bridge where the Lolo Pass Road crosses the Sandy River. Initially, major issues expressed by the riverside landowners included the impact of the Sandy River channel migration and intense recent flooding that resulted in adverse property impacts in January 2011. Residents were also concerned about possible damage in the future to roads, residences, bridges, and other infrastructure including erosive channel movement exposing or threatening water and sewer lines.

The Lolo/Zigzag Community feels an urgent need for effective flood response actions. They expressed intense anxiety about past flooding and trauma associated with watching neighboring homes destroyed in the January 2011 high water event. They want to be able to do something to protect their properties and are willing to continue to have a dialogue about ways to do so. Some residents acknowledge the potential of willing seller buyouts if restorative solutions cannot be found. Since the project site visit, three homes undermined during the 2011 flood event have been acquired by Clackamas County with FEMA funds. Residents remain concerned about their ability to implement flood response actions on properties that are now adjacent to county-owned land.

Impact from recent storms has made clear to neighbors that channel migration and lateral erosion pose imminent risk to some homes and infrastructure. We discussed some flood response alternatives including floodplain and side channel reconnection to redirect flows, dissipate energy, and reduce risk to property. Methods to reduce flood risk include alternatives to the bank armoring that has occurred in this area, such as the use and placement of large woody material.

Autumn Lane

Autumn Lane is a community on the mainstem Sandy at river left, above the Zigzag-Sandy River confluence. Residents described watching shorelines erode rapidly and streambank trees falling during the 2011 flood event, and the changing perceptions of the river and its risks they have experienced. One resident suggested, “You don’t have to convince me about climate change; we’re watching it happen right here” in the Sandy’s frequent floods since they bought and developed property.

They pointed out previous small in-river wood placements that were not successful in reducing erosion, as well as some riprapped banks that were now seen as potentially increasing vulnerability. One resident asked whether removing riprap would be considered as a potential future RFR action, changing the hardened streambank to a habitat-focused streambank treatment as the alternative.

One major concern raised by residents here is a problem with obtaining permits to conduct work on streambanks. They believe that this issue creates a roadblock for multi-landowner projects. Since individual landowners might employ different techniques to deal with the active riverbank changes, these residents are supportive of studies to give technical guidance. There is a strong desire among residents here to see action to fulfill the purpose of restorative flood response.

Flood Response Workshop at Sandy River Restoration Expo

As part of the council’s second annual Sandy River Restoration Expo on April 7, 2012 we organized a workshop with guest speakers from Interfluve, Cardno Entrix, Clackamas County and the U.S. Forest Service. County planner Steve Hanschka summarized the history of high water events on the Sandy, impacts from the 2011 flood event, and County efforts to develop a Sustainable Flood Response strategy, as well as ongoing floodplain re-mapping by state and federal agencies. County hazard manager Jay Wilson discussed flood insurance as an element of community flood response. He indicated that less than half of properties in channel migration-prone areas were covered by flood insurance, but that such coverage was applicable to assist with erosion damage from future events.

Forest Service fish biologist Kathryn Arendt, who has led restoration activities throughout the upper Sandy and Salmon Rivers, reviewed “What Salmon Need” – habitat conditions that are conducive to salmonid and ecosystem health, with an emphasis on local examples of large wood structures, natural and engineered, to help landowners conceive of the scale of appropriate actions. Arendt emphasized that various species of salmonids are in the Sandy system throughout the year, and throughout the basin, at various life stages, and how they are adapted to conditions of the river.

Interfluve geomorphologist Josh Epstein described design, analysis and implementation of streambank restoration projects, and showed examples of projects, which Sandy River residents could use as models. In particular, he examined the process of a streambank restoration along an access road in a migration-prone segment of the Klickitat River. Jenna Scholz from Cardino-Entrix compared actions in a Flood Hazard Management Plan for the Puyallup River basin in Washington, a large, dynamic glacial river, with potential Restorative Flood Response activities in the Sandy. She described stakeholder involvement, policy and analytical steps toward a flood hazard management strategy. Topics included constraints that affect flood hazard reduction actions, and potential opportunities that might exist in the Sandy. Scholz proposed a combination of Rapid Geomorphic Assessment and hydrologic modeling analysis as one approach toward developing specific conceptual project designs in flood-impacted Sandy neighborhoods.

Workshop participants asked what options were available to landowners whose streambanks were already undermined, or where channel migration had brought structures previously believed safe into risk from future events. Council staff and presenters emphasized that while some restorative measures might be effective, in some cases a property’s location in channel migration prone zones left little or no opportunity for effective actions.

Second Community Meeting

The second community dialog delved deeper into issues raised by community members in the initial discussion. This meeting was held on June 16, 2012 at the Welches Elementary School. Topics included methods to analyze and reduce risk, defining appropriate actions that would meet RFR goals in sample reaches of the Sandy basin, and funding opportunities for continued work.

Following a summary of field visits and issues raised in those on-site dialogs, Cardino-Entrix channel migration expert Jenna Scholz outlined the process of risk assessment, and steps toward effective risk reduction in dynamic river landscapes. Elements to consider include hazard probability, consequences of both no-action and alternative response actions, and costs. She also stressed the need for community stakeholder input in defining risk factors and responses. The presentation referenced ideas and approaches applied in channel migration zones of Washington state. She discussed a brief risk assessment approach applied to channel migration impacts in the Salmon River Park area, a neighborhood of 20+ homes on a peninsula at the confluence of the Salmon and Sandy Rivers. The Salmon River Park analysis indicated appropriate restorative responses including large wood placement, floodplain reconnection, and voluntary relocation. Scholz emphasized how proper risk assessment represented an application of the Precautionary Principle, resulting in plans that at least do not elevate risk.

Interfluve Inc. geomorphologist Josh Epstein explored conditions and data from the Timberline Rim neighborhood as an example of reach-scale planning, and steps necessary to define future projects. Timberline Rim is a development on both sides of the Sandy along a one-mile reach that experienced significant channel erosion and infrastructure impact in 2011 and earlier storms. Epstein showed time series images of the Sandy through the neighborhood reach since major alterations following the 1964 record flood. He emphasized the benefits of looking beyond single parcel streambank actions, and outlined component steps of conducting reach scale feasibility study, design, and implementation of potential restorative flood response actions. Eptein shared examples of comparable projects on the Lewis, Clackamas, and Klickitat Rivers to show the process of successful engineered habitat structures and interventions.

The Council discussed potential funding for continued RFR work. The Department of State Lands had submitted the project to a Federal Emergency Management Agency funding program for support, which lost out because of procedural concerns related to the Legislative Review Board cycle. The Council submitted a separate request to a FEMA RiskMap program grant competition that would further develop community scale project design options and produce a strategy handbook. Participants recognized that funding to assist community-based, multi-stakeholder projects would need to come from a variety of sources.

Description of Changes to the Proposal

Very little changed from the original proposal. We decided to engage two different professional consultants to increase the diversity of our technical expertise on this project. Additionally, we added the Autumn Lane residents to our site visits for increased community engagement. A snow storm on the scheduled date of our first meeting caused a delay and rescheduling, underscoring the climatic volatility the Sandy Basin can experience.

Public Awareness/ Education Components

Much of the RFR Phase I project focused on community education and engagement, as increasing public awareness on habitat-positive methods of reducing flood risk was a primary goal. Our initial community meeting in February 2012 attracted residents from each of the principal communities that had been affected during the January 2011 high water event, including officers from some of the homeowner’s associations. The site visits to individual neighborhoods brought in people who hadn't attended the community meeting and thus gave us the opportunity to hear from more riverfront landowners. Turnout for the second community meeting in June included residents from a number of the affected areas, and allowed for continued discussion on topics raised during individual neighborhood visits.

Clackamas County Dialogue

Through this process, a renewed, collaborative dialogue has begun among Clackamas County personnel and between the County, community members, and the Council on related issues of flood response. Internally, Clackamas County has started a working group to meet periodically and discuss sustainable flood response strategy. Additionally, the County has been encouraging public participation in the RFR phase I process. Two County-led “Flood of Information” winter preparedness events participants have further raised awareness of the impact of flooding within the county. Clackamas Water Environment Services (WES) has also reviewed ways to reduce impacts from and risk to sewage treatment along the Sandy, inviting Council input on streambank plantings at the rebuilding of the Hoodland sewer outfall infrastructure. Clackamas County also gained a national Corps of Engineers grant for a facilitator to continue community discussion of a possible flood district, including the Council as a member of the Flood Risk Advisory Group.

At a broad level, our meetings with residents, county elected officials and staff have helped shift the conversation from “put the river in its place” to a recognition that the dynamic nature of the Sandy coupled with the effects of climate change require a new approach to living with the river. Local landowners report that they have absorbed the background and channel migration maps on the “Restoration Resources for Dynamic Rivers” CD distributed at our meetings and community events. Because the council is seen as a non-regulatory but interested intermediary, we are helping to create a space for better decisions at the county level regarding policy and regulation related to channel migration.

Lessons Learned and Results

Restorative projects that channel migration and bank erosion are expensive, particularly if landowners are considering projects that consider reach scale river processes on multiple properties. Even when landowners may spend tens of thousands on individual streambank projects, reach-scale implementation is likely to require budgets beyond what is affordable for any individual, as well as additional planning and analysis.

Based on the response to our community meetings, site visits in neighborhoods, and conversations with numerous landowners, there is a high degree of community receptivity for the Council's efforts to explore and identify potential solutions. RFR Phase I has helped raise awareness, if not acceptance, of the role that large woody material plays in creating the complex habitat that salmon need. Projects recently implemented by individual landowners, and so far separately by county infrastructure agencies, indicate that people are willing to make significant financial expenditures toward solutions, creating an opportunity to channel community and public investment to more sustainable approaches that benefit salmon habitat

All four homeowners associations participating in RFR Phase I committed to continued work with the Council in a second phase of Restorative Flood Response. Timberline Rim’s homeowner’s association committed match funding for engineering design to connecting floodplain habitat upstream of the neighborhood and consider restorative streambank actions within the development’s one-mile reach.

A key outcome of RFR Phase I is that the council has brought community residents, agencies, and experts to the table for a candid discussion of the challenges and opportunities posed by living on the dynamic Sandy. The Council has a functional role as a non-regulatory intermediary working in the best interest of the river and local communities. Residents have demonstrated continued willingness and patience to participate in this dialogue despite some skepticism over the pace of regulatory review. Although some residents are frustrated by the pace of working through a process that relies on grant funding for project design and implementation, others recognize that the challenges on the Sandy River will take a new way of thinking, a number of years and some reach-scale projects to address.

With a community that has made continued substantial investments in infrastructure, including restoration, this provides an opportunity to capture successive investments. Building upon interest in this dialogue on habitat-positive techniques, we hope to leverage investments to ensure that future flood response includes actions that are ecologically restorative.

Recommendations

The project appropriately targeted resident landowners of flood impacted areas of the Sandy, Zigzag and Salmon Rivers. Through a variety of project activities, we also realized that streambank design and implementation practitioners are significant stakeholders and potential users of RFR information and approaches. The community workshops included some participation from local construction contractors, but targeted contractor education should be a component of future technical assistance. Like landowners, engineering and construction contractors may be unaware of the dynamics of the Sandy’s erosive potential. Also, engagement of county and other active public infrastructure agencies would be useful, given the continued use of river hardening in County agency projects where restorative practices might be more ecologically and cost-effective. Neither private landowners nor infrastructure agencies can apply restorative design standards or practices without a better understanding of how restorative, habitat-positive actions can meet shared goals regarding ecological conservation and community sustainability.

Appropriate demonstration projects on the Sandy mainstem can provide a localized example of Restorative Flood Response design and implementation that have been successful elsewhere. We also recommend developing a community RFR handbook and resource guide to create a common path for landowners, contractors, and regulators toward ecologically restorative, permissible, durable, affordable, and equitable solutions.

Special Conditions

There were no special conditions to this grant.